Written by Yuki Suenaga. Art by Takamasa Moue. Lettering by Snir Aharon. Translation by Stephen Paul. Published by Viz Media.

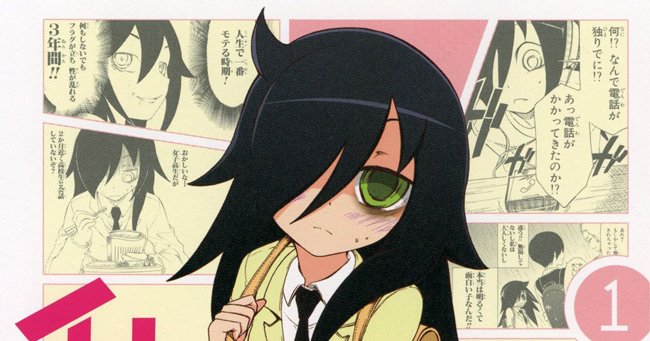

Just like its titular character, Akane, the manga Akane-banashi is one of the few Chosen Ones, having bucked the trend of Shueisha’s Weekly Shonen Jump axing series early in their publication. (See: Moriking, Majo no Moribito, Ayashimon, Super Smartphone…) It shares the magazine with a host of manga targeted at a younger male audience but is likely the most niche of recent titles. Somehow, Akane-banashi manages to be even more niche than Food Wars: Shokugeki no Souma, a cooking manga where food literally makes people’s clothes explode off their bodies. Centered around the performance art of rakugo, Akane-banashi’s continued success despite its obscure premise is part of what makes it so attractive.

What you just saw above was an example of rakugo. A modern definition might be a “sitcom where one person plays all the parts” but it has deep traditional roots, originating in Japan. “Kaidan-banashi”, “ninjo-banashi”, “ongyoku-banashi”, “nan-no-hanashi(?!)”. (have I gotten good enough at Japanese to make jokes?) – These translate to “ghost discourses”, “sentimental discourses”, “musical discourses”, and “what the hell are you talking about?!” respectively. Rakugo is a form of theatre that places weight on storytelling and wit, with a finesse that can be traced as far back as the Buddhist monasteries of 8th century Japan.

The manga’s title, Akane-banashi, is therefore an extension of these banashis – these types of stories or discourses. That makes the story both the cultivation of Akane’s Style as well as a chronicling of Akane’s Story.

There’s an appreciated sense of the crowd judging the rakugoka during their performance. It provides a sense of stakes for when you look back – an interface on how to pass judgement on what you’re seeing. You pay attention to subtleties, and look towards the experts to make sense of them. What’s truly happening during a scene is how the many diverse egos and personalities understand it to be, typically with their own bias on what “proper” rakugo is.

The story begins with the rakugoka Shinta Arakawa. Or rather, it starts with his daughter Akane, drawing parallels to the early dynamic of Shanks and Luffy from the popular manga, One Piece. The influence Shinta has on a young Akane is profound. He sticks to his principles in a way that hurts to watch and is embarrassing to his loved ones. He’s a coward but a painfully honest and kind man too. It’s a classic case of burdening a child because it forces Akane to fight the world just to continue to see Shinta as her hero. To be frank, Shinta Arakawa is a wetwipe. That’s how society defines him to be. He knows this and stakes everything on the exams that will take him to the most senior rakugoka position: The Shin’uchi promotion exams.

When it’s on the rakugo stage at least, the label of “deadbeat father” doesn’t apply unless he’s playing a character. He’s either good or bad. A fool for skipping the makura or a brave soul. However, you can’t quite shake that sense that he’d prefer someone slander his name or spill a drink on his head than see his daughter defend him out of anger. He practises rakugo, an art form centred on communication, but unlike Shanks, never quite prepares her for the fundamental question that the first chapter proposes: What are we then, if not defined by others?

For a manga based on communication, the least you can expect is the creative team keeping you in the fold. Artist Takamasa Moue’s contrast of dark and light throughout the performance are like little primers. Pressure, tension, buildup – lighting isn’t restricted to any particular emotion which allows for depth in storytelling.

Demonstrating his will, narrow panels like the one above use dark action lines to highlight Shinta’s powerful stage presence, yet the continued use of dark tones paints a contrast between opposing emotions – tentative confidence and depression. Moue’s skillful use of tone means that you smoothly step through emotions. You feel where the story will go before it arrives. Shinta passing the exam was too good to be true, but for me, the expert opinions littered around meant all I could do was rely on how they and the crowd defined the performance.

Pulled from the theatre, Volume 1 delves into a bit of the politics of the rakugo world, establishing friends, rivals and philosophies. It also introduces Issho Arakawa, one of the greatest rakugoka of his generation and a senior Shin’uchi of the Arakawa rakugo school. Built from Shinta’s ashes, having crushed his dreams onstage, Issho is the embodiment of a cardinal rule being broken and thus a villain personified. After all, if it’s the crowd who defines you, then how could he come and unilaterally expel Shinta?

In just one chapter, a small man is built up into a giant onstage and then crushed without a second thought. It’s not a story to get overly sad about. After all, the point of view quickly shifts to Akane, who grows and seeks to dominate others using her inherited skills. She’s an avenger, whose father’s crushing remains a mystery even after Volume 1. Akane will race through the ranks such as Zenza, Futatsume, and Shin’uchi, detailing stories that Western audiences might feel alienated by.

While Akane is not someone who knows how to compromise with a crowd, Yuki Suenaga crafts every chapter with a far gentler touch. He’s aware that the reader is being exposed to a new artform for the first time, and so weaves characters, histories and the reader into a central theme. A theme of carrying. Akane learns to carry her burdens, her arrogance, but also her failures.

Carrying these lessons, the joy of reading Akane-banashi comes from watching her adapt to her circumstances in unpredictable ways, yet still in a manner that feels very Akane-like. Suenaga ensures that the reader carries too – that they’re well-equipped to come along for the ride. You’re not obligated to start your own Anki deck of traditional Japanese words.

This means there’s more than enough scope to studiously or casually pick up understanding. Our ability to appreciate rakugo is woven into character arcs, opportune times for readers to apply what they know. Akane’s quip in Chapter 5 – that “it’s all about skill” sticks out like a sore thumb when you’re used to shonen tropes, but more studious readers can apply learned concepts such as kibataraki, appreciating it from that perspective too. Akane’s introduction to rakugo was seeing her dad’s dream rubbished on stage. With that chip on her shoulders, she was always going to lack certain foundations. The enjoyment in the journey is refining our understanding through seeing what she lacks – seeing Akane’s Style, or we can enjoy her swallowing up her rivals through grit and friction. In other words, Akane’s Story.

Or you can craft the experience however you wish. Just as no one would judge you for reading this manga and then flying to Japan for a rakugo performance, this manga is also just a cool character carving out her place in hostile territory.

Suenaga’s attention to keeping the reader involved in the rakugo culture means we share in the awe of Akane succeeding despite the odds, as well as relishing the sweet moments. He and Moue’s ability to convey information clearly, as well as the expressive charisma of the characters leave you grinning alongside the characters without you realising it.

What the Akane-banashi creators are trying to accomplish here is by no means easy. A title about rakugo that grounds itself in realism while competing against pirates, mafia, and demons in the same magazine is an audacious task. Akane-banashi represents a feel-good story of someone creating their style, and the pair of Suenaga and Moue ensure you’re in the best seat to enjoy the show. There’s an energy in every character’s facial expressions, and a force in the stage presence of both rivals and allies. While Akane-banashi might deviate from the norm, its execution lands in that familiar, inspiring way that manga fans have come to love. This makes it the perfect intro to manga, a continuation of your manga journey, and an impetus to dive deeper into Japanese culture.

Akane banashi is published by Viz Media and the first and latest three chapters can be read for free on VIZ’s Shonen Jump service. Volume 1 will be released on 8th August, 2023. You’ll be able to find it at all good comic book shops, online retailers, and Amazon/Kindle.

Leave a comment